Advent Of Code 2022

Advent Of Code 2022

By Dmitri Sirobokov

15 min read

Advent Of Code is a set of puzzles that will test your problem-solving skills using your favourite programming language. You do not need extensive programming skills, but the knowledge of some standard algorithms is a pre. Plus, it is a lot of fun and a very exciting way to challenge yourself.

- Authors

- Name

- Dmitri Sirobokov

It's been almost three months ago since I heard about Advent Of Code for the first time. At first, I didn't pay any attention, until I got an invitation link from my colleague to join. My colleague showed me a few interesting puzzles from the previous year, and I suddenly became very interested in them.

The Advent of Code is an Advent Calendar of small programming puzzles that can be solved in any programming language that you like. Every year, starting from 1 December til 25 December you will get a new puzzle daily, 25 puzzles in total. It is free and anyone can participate. You can visit the site and try to solve any puzzle from past years. People use them for interview prep, company training, university coursework, practice problems, a speed contest, or to challenge each other.

It would be a big and boring blog if I post every puzzle here and explain how did I solve them in detail. I don't want to spoil the fun if someone is looking for a solution themself. Instead, I want to share my experience and what did I learn from it and give a couple of examples of common problems, which I found very interesting (and challenging). In the end, you will find a link to the GitHub repository with all my solutions. Have fun!

Experience

Puzzle Format

- Every puzzle has two parts. Part 1 is usually where I was thinking "Oh, I got it!", and Part 2 usually comes with a surprise :-) Solving one part of the puzzle rewards you with a Star. Solving a complete puzzle rewards you with two Stars. You need 50 stars to complete Advent Of Code.

- Every puzzle has a test example.

- Every participant of Advent Of Code gets personalized input to the puzzle. If you run this input through your program and the result is correct you will get a Star.

- There is a Global Leaderboard with rankings; if you want to compete with the whole world! But you can also join any of the Private Leaderboards. I joined a small group of iO colleagues and we had our own Private Leaderboard.

Time

The first few days when I started, it took me around 30 minutes or quicker to find the solutions. So I could just wake up a bit earlier before going to work. As complexity increased almost every day, it took me more than an hour or two. I had to use my lunch breaks for it and time in the evenings. And then there were a couple of problems that took me more than a day to solve. But roughly, I think I spent on average 2-3 hours per puzzle. That is 50-70 hours in total! That is a lot! And it won't go unnoticed. My advice, make an agreement with your friends, partner or with yourself if you want to find some time for it.

Typing skills

After typing hundreds of for-loops, I wish I could think and type as quickly as Victor Rentea and I wish I watched his videos before. That would save me so much time. Something to learn for the next time!

Programming language

You can choose any language of your preference. I saw some guys writing all solutions in SQL :-). The Advent of Code is a good opportunity to learn a new language. However, I am glad to stick to Java (my favourite is C#). Learning a different language and the ability to solve problems are two different things. But you can do both of them at the same time, of course, if you want to challenge yourself even further.

Working with Java for the last 7 years, I was surprised to struggle with basic functionality. I found that there is so little support for primitive types, which is needed for the performance when you are dealing with large 2D arrays of integers, like int[][]. You can not create generics of primitive types, for example, Map<long, long> is not allowed. It must be Map<Long, Long>. Map.get(13L) and Map.get(13) produces two different results without any type check. I encountered so many bugs because of that. You need constantly box and unbox between int and Integer, or many operations and methods are not available on int-type. Many stream operations (like finding max value) are different when you perform it on IntStream (that implements primitive int-type) and when you use Stream<Integer>, so you have to use some utility methods to convert between each other. I found myself abandoning the idea of using streams in many calculations, in favour of writing a simple for-loop.

Test-Driven Project Setup

Every puzzle provides you with a sample input and the answer for that input. It is a perfect setup for Test-Driven approach. I could use unit tests to run and debug my solutions directly from IntelliJ IDE and test the code when I improve solutions.

+- src\

|

+- main\

| |

| +- java\

| |

| +- dms.adventofcode\

| |

| +- y2022\ # Folder that contains solutions for each day of Advent Of Code 2022

| |

| +- Day1.java

| +- Day2.java

|

+- test\

|

+- java\

| |

| +- dms.adventofcode\

| |

| +- y2022\ # Folder that contains test cases for each day of Advent Of Code 2022

| |

| +- Day1Test.java

| +- Day2Test.java

+- resources\

|

+- y2022\ # Input to your puzzles

|

+- day1.txt # Your real input to the puzzle Day 1

+- day1_sample.txt # Sample puzzle input for the Day 1, for which the answere is provided.

+- day2.txt

+- day2_sample.txt

One more thing to mention here. Starting from Day 5, I am using parameterized unit tests. I came across this Guide to JUnit 5 Parameterized Tests to figure out how to extend my JUnit framework using ArgumentsProvider interface. I have removed duplicate code that reads sample files for my test cases. My code became at least 2x shorter and cleaner after that:

class Day08Test {

@ParameterizedTest

@TestInput(input = "y2022/day8_sample.txt", expected = "21")

@TestInput(input = "y2022/day8.txt", expected = "1849")

void part1(List<String> input, int expected) {

var result = Day08.part1(input);

assertEquals(expected, result);

}

@ParameterizedTest

@TestInput(input = "y2022/day8_sample.txt", expected = "8")

@TestInput(input = "y2022/day8.txt", expected = "201600")

void part2(List<String> input, int expected) {

var result = Day08.part2(input);

assertEquals(expected, result);

}

}

Classes of problems

Integer overflow

Many of the problems include operations where int-type values become too large. 32-bit representation is not enough and the value overflows. I did not get any runtime exceptions, the result of the calculations is just wrong. Looking at the result I could see a large or negative value. This is usually a hint that I have to check if there are any operations where the number could overflow. There are a few approaches to this problem: use long-type, use mod-operations, and find common dividers to reduce the value range.

Parsing (Nested) Expressions

Every puzzle starts with input data that you have to parse before you can use it in your puzzle. But a few of the puzzles go further than that, for example, when input contains a math expression and you need to evaluate it. I have not found a generic way to do that, so I reinvented the wheel every time. I've made a note for myself to do some more research about it the next time.

NP-Complexity

NP term comes from the complexity theory of algorithms and is short for Nondeterministic Polynomial time problems. It is an exciting area of research, probably the most extensive one in computer science at the moment, especially with a related study of Quantum Computing. You can check out more about it here or here. But if you want to skip all theoretical stuff, the most important you need to know is that NP problems are decision graphs that require exponential computational time and often large memory space. Using the traditional approach might take years of calculations even for small-size graphs. To overcome these difficulties, requires some creativity, such as:

- Try to break down the problem into smaller problems for which faster algorithms already exist.

- Observations. Find some parts in the decision graph, that you can skip from the calculation; because you can prove they will never lead to a solution.

- Dynamic Programming. Memorize similar parts of the decision graph such that you need to calculate them only once.

A few interesting puzzles

I found most of the puzzles quite interesting and challenging, but I will mention a few of them just to demonstrate what I said above.

Day 11: Monkey in the Middle

Type of the problem: Integer Overflow

Solution: Find a common denominator.

Many of us know the game from childhood when kids are standing around and passing the ball to each other. You are standing in the centre of the circle and trying to catch the ball. They call it 'Monkey In The Middle'. Except that in this puzzle you are now the one who stays in the middle and monkeys are around you throwing items which they stole from your backpack. Where a monkey throws an item depends on whether the monkey can divide your stress level, integer argument, by a certain number. After many rounds, you need to figure out which monkey to chase (the most active monkey, which has most of the items).

The problem with this puzzle is that your stress level grows quickly with each round. You will not notice that in Part 1 of the puzzle, however, in Part 2 it is growing exponentially and the value runs out of the maximum range pretty quickly, even long-type value (64-bit) will not save you.

Imagine your stress level is X.

Monkey A decides where to throw the item if X is divisible by 8.

Monkey B decides where to throw the item if X is divisible by 12.

After each round X is increased by 3.

The pseudo-code (simplified) would look like this:

long x; # Holds your stress level

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

# Monkey A

if (x % 8 == 0) throw_item_to_monkey_C();

# Monkey B

if (x % 12 == 0) throw_item_to_monkey_D();

# Stress level increased

x = x * 3;

}

You can see that the X argument will overflow in about 50 turns (if long-type). But we need to simulate 10000 turns.

One thing to notice about modulo operation is 8 % 8 is the same as 16 % 8, or 24 % 8, 32 % 8, etc. We do not need X to be higher than 8 for this operation. We could just limit it with x = x % 8;. However, if you do it just for monkey A, that would not hold for monkey B, because it uses 12 for the division test. The trick here is to find the number that works for both monkeys. And it is very easy. Just multiply both numbers 8 and 12, which is 96. This number, which is called common divider (or common denominator) will always work for both monkeys.

With that in mind, we can limit X to the maximum value of 96 and the above pseudo-code after correction would look like this:

long x; # Holds your stress level

for (var i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

# Monkey A

if (x % 8 == 0) throw_item_to_monkey_C();

# Monkey B

if (x % 12 == 0) throw_item_to_monkey_D();

# Stress level increased

x = x * 3 % (8 * 12);

}

If there are a lot of monkeys, the common denominator might also become too big and will not fit into long-type. However, it didn't happen in my puzzle input. I had only 7 monkeys and all of them were using small numbers. If that would happen, I still could improve the solution by applying the Euclidian algorithm to find greatest common divider. In the example above greatest common divider is 24.

This technique is very common for encryption and compression algorithms to reduce repetitions or remove redundant information.

Complete solution in GitHub: Day 11

Day 12: Hill Climbing Algorithm

Algorithm: Dijkstra (or Bfs).

In this puzzle, we have to find the shortest path to the top of the mountain. When I hear the "shortest path" I almost immediately think about Dijkstra. The algorithm is developed by Dutch computer scientists in 1956 and became the most popular algorithm in navigation systems which everyone is using nowadays. I would recommend everyone to learn how it works and this puzzle is an excellent occasion to practice your implementation. It is fun.

Alternatively, I could choose another algorithm: Bfs. Under some conditions, Bfs typically has better performance and is simpler than Dijkstra, but I've chosen Dijkstra because I wanted to learn it better.

Dijkstra is a Single-Source-Multiple-Destinations path-finding algorithm which comes especially handy in Part 2 of the puzzle, where you need to calculate all possible starting locations to reach the top of the mountain. With Dijkstra, you run this algorithm just once.

Another cool thing about Dijkstra, it works the same with no performance penalty when the distances between nodes are different. That makes much broader use of this algorithm.

Check it here for more comparisons.

Complete solution in GitHub: Day 12

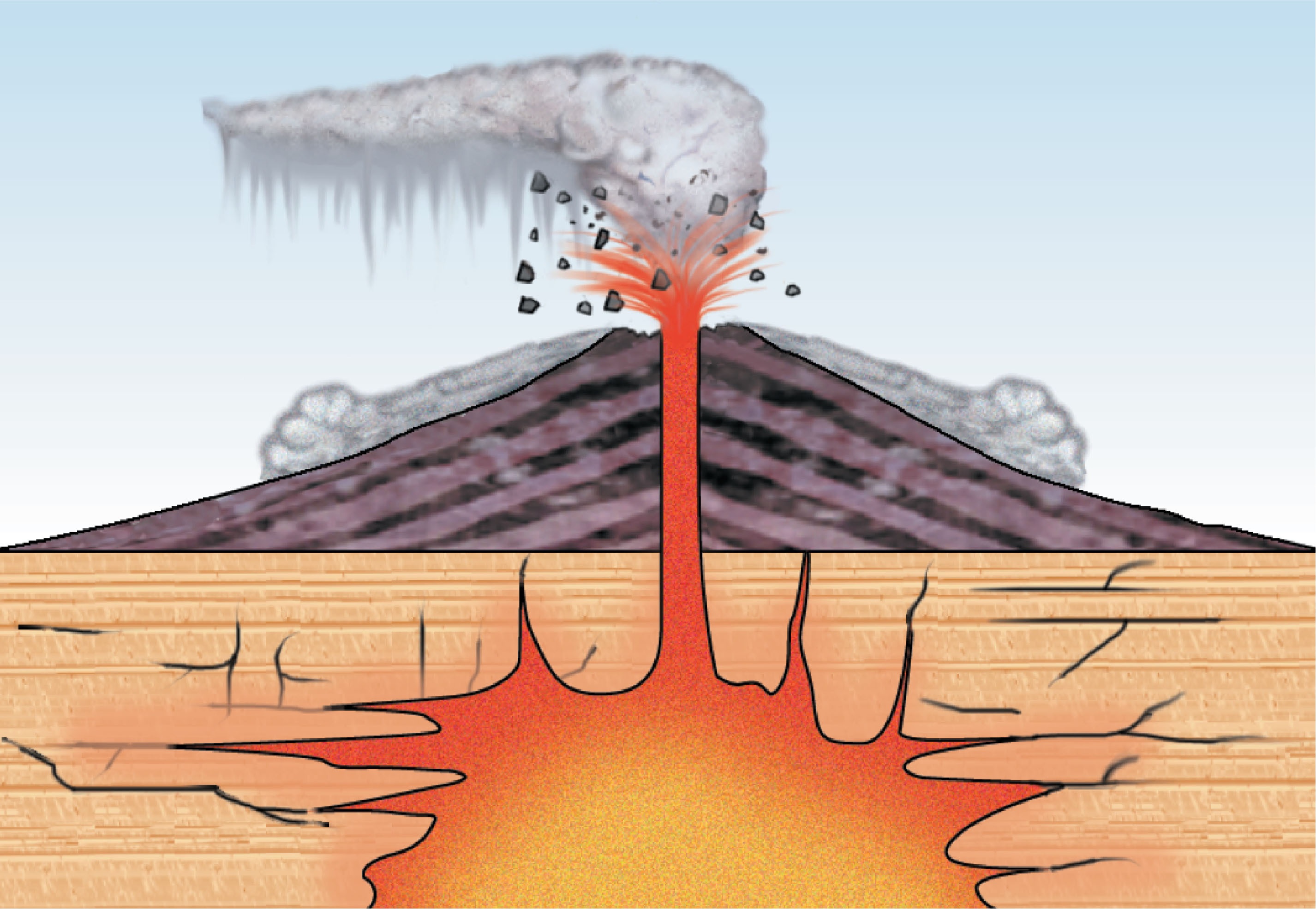

Day 16: Proboscidea Volcanium

In this puzzle, I have to prevent a volcano from an explosion. To do that we have to open many valves which are installed in different chambers inside the volcano. Each valve releases the pressure from the volcano at a given rate per minute. It takes one minute to go from one chamber to another and it takes one minute to open the valve. I have 30 minutes to open the valves and I need to find the best possible sequence that releases most of the pressure.

My original idea was to find all possible independent paths using Combinatorics, which worked pretty well in Part 1 of the puzzle, but Part 2 of the puzzle is a bit tricky. In Part 2, I can train an elephant (second player) for 4 minutes then it will start to help me to open valves. I need to find the best sequence of valves for myself and the elephant. This is a part where I struggled for a few days. I could not find a good algorithm that works quickly (after 2 hours my program was still running) for both Part 1 and Part 2.

I finally gave up on that idea (I might come back to it later) and reached out for some hints on Reddit. The hint that I used was pretty simple. I can use Dfs search algorithm recursively, first for myself, and then for the elephant (second player). As soon as I reach the last valve (leaf node in the graph), I let the elephant open valves but avoid valves that are already open.

private static int dfs(ValveGraph graph, Valve currentValve, long openValves, int remainingTime, int otherPlayers) {

if (remainingTime == 0) {

return otherPlayers > 0 ? dfs(graph, graph.startValve, openValves, 26, otherPlayers - 1) : 0;

}

...

}

Interesting Facts

Did you know that people tried to drill a mountain in real to reach magma and tried to release pressure inside? These are famous projects:

- 1989-1998, a drilling project in Long Valley, California

- 2005, Hawaii, Puna Geothermal Venture

- 2009, Iceland, Krafla Power Station

So far these attempts are not succeeded, but they sparked a lot of scientific research to study the behaviour of magma. If you are interested, you can read more about it here.

Complete solution in GitHub: Day 16

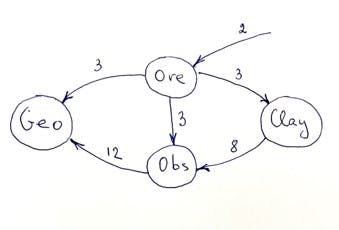

Day 19: Not Enough Minerals.

| Ore | Clay | Obsidian | Geode |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Algorithms Used:

- Dfs

- Dynamic Programming

In this puzzle, we need to produce as many Geodes as possible within 30 minutes. To produce a mineral we use robots, but to create a robot we also need a set of other minerals. We can create only one robot per minute. As soon as the robot is created, it starts to produce 1 mineral per minute. For example, we have this blueprint from the puzzle:

Each ore robot costs 2 ore.

Each clay robot costs 3 ore.

Each obsidian robot costs 3 ore and 8 clay.

Each geode robot costs 3 ore and 12 obsidian.

If I draw a flow diagram, it will look like this:

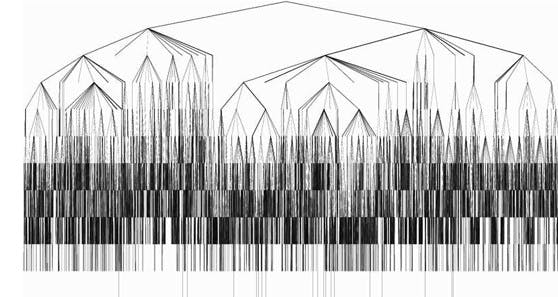

This is an NP-type problem. Every minute we have 5 choices (to create one of the 4 robots or skip one minute). If we construct a graph from those choices, after 2 minutes we will have 25 nodes, after 3 minutes 125 nodes, and so on. After 30 minutes that will be about 10^20 nodes! If we would need to simulate 100 minutes we would have more nodes than all atoms in the Universe. That is how NP-complexity grows exponentially:

The goal here is to search through all leaf-nodes in the graph for maximum value using Dfs, but we need to find a way how to reduce the number of nodes so our programs can finish within a feasible amount of time. These are optimizations which I applied to reduce the number of nodes, based on some observations:

- It does not make sense to produce more robots than the maximum cost of the robot, because we start to generate more resources than we can spend.

- If we have more material than we ever can spend in the remaining time, then we do not need to produce more robots of this type.

- Dynamic programming. If you are new to it, you can check out a few links about Memoization and Dynamic Programming.

Currently, I have around 10-20 bn. nodes after those optimizations, and it takes around 25 sec to execute Part 2 of the puzzle. I heard some people could make it under 1 sec. So there is still a lot of room to improve here :-)

Complete solution in GitHub: Day 19

Conclusion

What I found amazingly good in Advent Of Code is that it is made in such a way that it does not require any high-level programming skills. After all, it is more about the ability to solve a problem and not the ability to write high-quality code (what is one without another?). But of course, along the way, I noticed improvements in the coding as well.

I was always passionate to learn new algorithms. Prior knowledge of algorithms is not required, as long as you understand the problem and have an idea of how you would solve the problem you can reinvent most of the algorithms used in Advent Of Code, or do some research for existing implementations. I see it as tools, the more tools you know, the easier it will become to solve the problem.

Handy List of algorithms, that I recommend reviewing:

- Binary Search (Day 15)

- Bfs

- Dfs

- Dijkstra (Day 12)

- Euclidian

- Number Base Conversion, modified version (Day 25)

And if you want to learn more algorithms here is a great link to start.

Finally, this is a link to all my solutions for Advent Of Code 2022:

https://github.com/dmitri-sirobokov/advent-of-code